“The story of human history is a story of building, perpetually building to accommodate actual and imagined needs…But in truth, nature shapes how people experience the environments they build. Our human bodies…evolved over tens and hundreds of thousands of years by adapting to nature’s forms and rhythms, by successfully confronting its challenges and seizing its opportunities, by discovering safety in its sheltered corners and possibility in its airy expanses. Our bodies flourish and perish on this and no other earth: we thinking, breathing, sentient creatures sleep when it’s dark and amble in the light, drink and bathe in water and consume its animal and vegetable offering until, when it’s time, we dissolve to dust.”

This post comes a bit late, to say the least. Completing the Travel Fellowship was a whirlwind, with trying to finalize the written portion of the book upon my return from visiting and touring the case studies, and packing up to leave San Francisco for my new adventure in Europe. I spent the remainder of the summer traveling across the old continent working on a research grant I was awarded by RISD. Not to make excuses, but the start of the school year took me by surprise, and work on my master thesis proposal took over. As such, finalizing my Fellowship report (next blog post) and getting approvals to share with the broader audience took some extra time. So there you have it, a big, fat excuse 🙂

The winter break allowed me to take the time and contemplate the amazing summer I had in 2018! I have traveled a ton, learned a lot, and met some amazing people, both at Hart Howerton and at the case studies I visited (more details in the next post that includes the report.) In this post, I’d like to include the places I visited on the West Side of the United States during the final leg of my Fellowship travels. But before I do so, I’d like to briefly discuss the Nature Deficit Disorder (NDD,) as defined by Richard Louv in his seminal book, Last Child in the Woods.

According to Louv, Nature Deficit Disorder (NDD) affects most children [and adults] in the developed world. Although not an official medical term, NDD is an idea that spending most of the time indoors – and apart from nature – negatively impacts children’s mental and physical health. Research studies show that exposure to nature (in both directed and indirect ways) improves creativity, attention, and test scores (Terrapin Bright Green.) Biophilic design is a human-centered design approach that focuses on re-establishing the vital human-nature connection, and can be used to prevent the NDD when applied to our built environment.

We spent most of our time indoors, and the past few decades have seen an exorbitant decline in the time children spend outdoors. According to a University of Maryland study of American children, there was a 50% decline in time children ages nine-twelve spent on outdoor activities between 1997-2003! As Louv states, “as far as physical fitness goes, today’s kids are the sorriest generation in the history of the United States. Their parents may be out jogging, but the kids just aren’t outside.” This issue is not unique to the USA alone. As Louv writes, “The Daily Monitor,published in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, issued a plea in March 2007 for parents to get their children out of the house and into the outdoors, noting that ‘many Ethiopians will have reached adulthood far removed from outdoor experiences.’”

Louv describes the grave costs of alienation from nature, “among them: diminished use of the senses, attention difficulties, and higher rates of physical and emotional illness.” In her book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, Sarah Williams Goldhagen states, “Natural light, like pastoral vies, heals the sick and improves the well-being even of the well by affecting our cognitive processes in profound, though sometimes subtle ways…children in properly lit classrooms focus better, retain information better, behave better, and score better on tests. Daylight measurably affects people’s moods…and is proven palliative that alleviates the symptoms of mental illness.” She continues, “we are so biologically wired to embrace the natural world that, in addition to greenery and light, we respond strongly to natural materials, biomorphic forms, and specific topographic features. These include ones that were critical to the African savannah, where our ancestors thrived for tens of thousands of years: gently rolling hills, even ground covers, meandering pathways, and copses of trees and shrubbery that screen illuminated clearings.”

It is clearly imperative that both children and adults spend more time in nature. However, if we must be inside, let the built environment reflect and remind us of the natural world of which we are a part, through biophilic design. My wish for this New Year is that we all make more of an effort to get outside and enjoy the natural world. I hope that more projects incorporate biophilic design, as we create more healthy spaces that benefit not only the human users, but also the natural environment at large.

Wishing you all a happy, healthy and a biophilic New Year!

Below are the case studies I visited during the last leg of my travel Fellowship.

1. Bullitt Center, Seattle, WA by the Miller Hull Partnership,2013 (52,000 ft2)

2. Amazon Spheres, Seattle, WA by NBBJ, 2018

3. Bertschi School Living Science Building, Seattle, WA by KMD Architects, 2011 (5,225 ft2)

4. Case Middle School, Punahou School, Honolulu, HI by John Hara & Associates, 2004

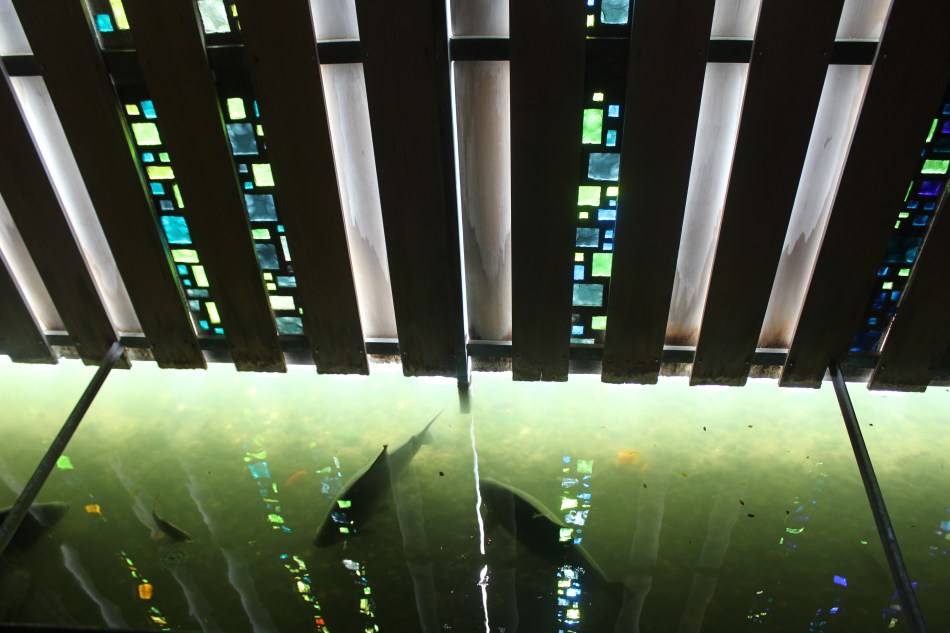

5. Thurston Memorial Chapel, Punahou School,Honolulu, HI by Vladimir Ossipoff, 1966

6. The Liljestrand House, Honolulu, HI by Vladimir Ossipoff, 1952

7. IBM Building, Honolulu, HI, by Vladimir Ossipoff, 1962

8. University of Hawaii, West O’Ahu Campus by John Hara & Associates, 2012

9. Energy Laboratory, Hawaii Preparatory Academy, Waimea, HI, by Flansburgh Architects, 2010 (6,100 ft2)

10. Davies Chapel, Hawaii Preparatory Academy, Waimea, HIby Vladimir Ossipoff, 1966

11. West Hawaii Explorations Academy, Kailua-Kona, HI by Ferraro Choi Architects, 2014

12. Community College of Hawaii, Palamanui, Kona, HI by Urban Works, 2015

“Genetically we are predisposed to crave and take a singular kind of pleasure in environments where nature’s presence is palpable…we embodied humans have evolved as a biophilicspecies; meaning that we are drawn to nature: we like to feel a connection to it in our homes, our offices, our communities. Our very genes are encoded to link our well-being – our beingwell and our feelingwell – to sustaining an intimate connection with the natural world. This applies to urban dwellers and to country folk, to people in all kinds of environments, to people of every ethnicity.”

0 comments on “West Coast & Hawaii Case-Studies”